The Data Distribution

How to choose your tech stack in 2026

How tech stacks are chosen

Choosing a tech stack for your product has historically been a decision influenced by mimesis, pragmatism, familiarity, and neomania.

mimesis - Google uses Go, I want to be like Google, therefore I should use Go.

pragmatism - C++ is performant and the most widely used language for game engine dev, therefore I’m going to write my game engine in C++.

familiarity - I know Java best, therefore I’m going to use Java.

neomania - Irrational desire that conflates “newness” with “goodness”, causing you to choose the hot new language you read about on Hackernews. Ex. Zig.

Good code exists with any stack, and so does bad code

When a developer starts a new job, they’re often working in a new (to them) programming language, with a new set of technologies on a completely foreign codebase. Task by task, they gain familiarity with the new language and in a few months, its syntax gets etched into their neural pathways. After this point, the greatest determinant of how much they can output in the new codebase relative to previous codebases they’ve worked on, is the architecture and health of the codebase. Good documentation, good tests, and decoupled code allow them to move swiftly with confidence. No documentation, poor test coverage, and highly coupled code cripples their pace, as the amount of time needed to confidently add functionality without breaking the world is increased by several orders of magnitude.

Massive paradigm shift

In 2023 Andrej Karpathy made a prescient tweet that jokingly stated “The hottest new programming language is English”. Fast forward 3 years to 2026 and that joke is becoming a reality.

LLMs can now effectively compile English to large amounts of code in the language of your choosing. Yes, you still need to be able to read and evaluate that code, the design decisions made, and the overall architecture, especially if you work on a complex product with real users, but your ability to do this is also greatly enhanced by LLMs. Frontier models can give detailed explanations with fancy ascii diagrams and example data explaining all of the code they write, the data flows introduced, and what it looks like at execution time.

The Data Distribution

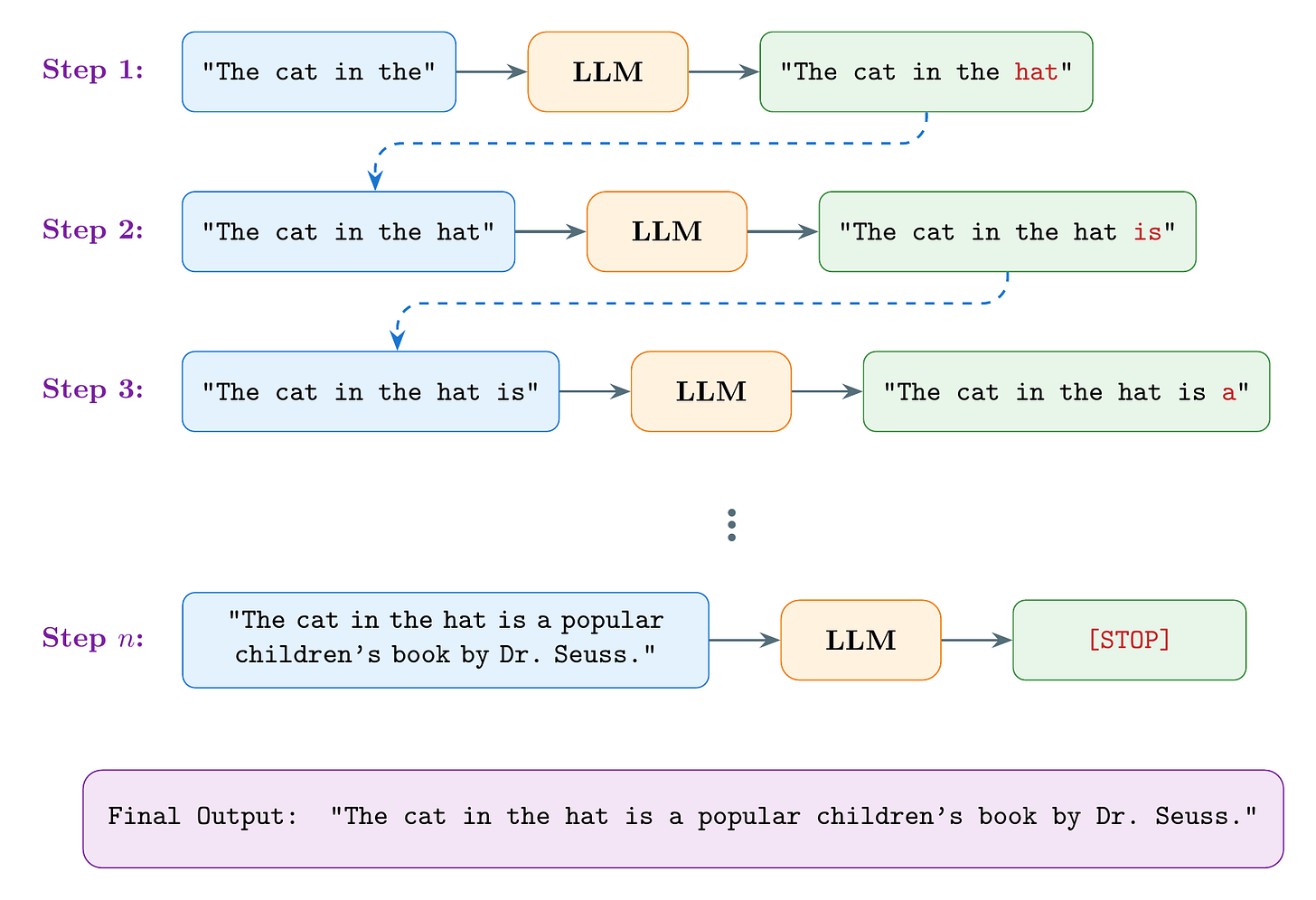

LLMs are next word predictors. Given a sequence of text inputs, they predict which word (or part of a word) is most likely to come next. For example, given the input: “The cat in the”, they will predict the next most likely word to follow, which in this case could be “hat”. They then take this output and feed it back into themselves as the next input. They continue this process in a loop until they predict that the next most likely sequence of text is actually to stop.

Example

How does the LLM know which word is most likely to come next? This depends on the type of data that was used to train the model, also known as the “data distribution”. If the model’s training data included a bunch of children’s books, there’s a good chance that the next token they predict from the input “The cat in the” is “hat”. But if their training data had no children’s books, they might predict something like “litter”.

When LLMs are used to produce code, their outputs are going to be best on the types of code they saw the most of during training. If an LLM is trained on trillions of lines of python code but only a few million lines of javascript code, it’s going to be much better at writing python than javascript.

Programming languages, frameworks, and technologies that are very prevalent in the training data of LLMs are known as “in-distribution”. Esoteric languages and technologies that are not very common in an LLMs training data are known as “out-of-distribution”.

Choosing a stack based on how ‘in-distribution’ it is

Now suppose we live in a world where developers program primarily in English: providing context and instructions on what they want to an LLM, which then transforms that English into code. The timeline for onboarding has been compressed from months to weeks, as each developer has 24/7 access to the original author of the code, who can explain every line and answer all of their questions. In this world, one of the most important factors for speed and the quality of features shipped is whether or not the chosen stack is in-distribution. This will result in a healthier, more changeable codebase, which will in turn improve the rate at which the LLM can make further changes to said codebase.

You can test out the concept of “in-distribution” vs “out-of-distribution” tech stacks yourself by building the same project in Python (very in-distribution) and Zig (very out-of-distribution) and observing how much better the Python output is than the Zig output.

Recommended “in-distribution” stacks

The frontier model companies: OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google, aren’t super transparent about the exact datasets they use to train their coding models, but I have pretty high confidence that their primary source of data is GitHub. On his recent appearance on the Dwarkesh Podcast, Ilya Sutskever, co-founder of OpenAI and now founder of Safe Superintelligence Inc. mentions in passing that the frontier models are trained on the entirety of GitHub. I also found (with the help of Claude Research) Open AI’s first paper on Codex, which explicitly states that the model was fine-tuned on publicly available code from GitHub, and particularly focused on writing Python code. It’s worth noting that Dario Amodei, Sam McCandlish, and Jared Kaplan were co-authors of this paper and went on to found Anthropic, so it seems likely that they took with the practice of training on GitHub with them. Anthropic’s Opus 4.5 Summary Table states that Opus 4.5 “was trained on a proprietary mix of publicly available information from the internet up to May 2025, non-public data from third parties, data provided by data-labeling services and paid contractors, data from Claude users who have opted in to have their data used for training, and data generated internally at Anthropic.”

So what are the most “in-distribution” languages, frameworks, and databases on GitHub? Well according to Octoverse 2025, GitHub’s year-in-review statistics blog post, the top programming languages on GitHub from 2023-2025 are:

JavaScript/TypeScript

Python

Java

C#

PHP

C++

Shell

C

Go

With JavaScript/TypeScript and Python having substantially more contributors than the languages below them.

Octoverse 2025 doesn’t mention the most popular web frameworks or database technologies, but we can confidently infer them by looking at a combination of Stack Overflow’s 2025 dev survey, GitHub stars, and package manager downloads (PyPi/NPM).

Frontend Frameworks

React - 242k stars, 53.8M weekly downloads

Vue - 52.7k stars, 7M weekly downloads

Angular - 99k stars, 3.8M weekly downloads

Backend Frameworks

Express.js - 68.5k stars, 53.9M weekly downloads

Django - 86.4k stars, 22.5M monthly downloads

Spring Boot - 79.6k stars, most popular on maven

Databases

PostgreSQL

MySQL

SQLite

Source used: https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2025/technology#1-databases

So if you’re looking for a data-driven recommendation on the tech stack that Claude or Codex will be most competent with, the data says:

TypeScript, express.js backend, react frontend, PostgreSQL database

Python, Django backend, react frontend, PostgreSQL database

Java, Spring Boot backend, react frontend, PostgreSQL database